Equine Wellness: Anhidrosis

Summertime has now hit Florida in full force. With our extreme temperatures and humidity, we start to see an increased occurrence of anhidrosis in our horses. Anhidrosis is the absence of an adequate amount of sweat in response to an increase in body temperature. Often, we call horses with anhidrosis a “non-sweater.” This absence of sweat can lead to severe clinical signs; onset can be gradual or acute. This problem especially affects performance horses because they utilize sweating for thermoregulation. Studies have shown that horses lose 60-75% of body heat via sweat evaporation. Humid environment decrease the efficiency of sweat evaporation and cooling. If a horse is not sweating at an appropriate level, it puts the horse at risk for hyperthermia or heat stroke.

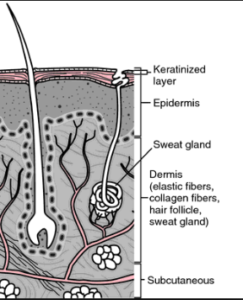

Anatomy and Physiology of Sweat

Sweat glands are densely packed in the horse skin, usually around the skin surface at the hair follicle. These glands have a large amount of blood supply and nerves close to the glands. Sweat is made up of mostly water but also contains proteins and electrolytes. Electrolytes in sweat (sodium, potassium, chloride) are found in much higher concentrations than blood.

Cause of Anhidrosis

At this time, there is no known specific cause of anhidrosis. Previous suggestions include hypothyroidism, low chloride concentrations, and elevated epinephrine levels. These have not been consistent findings in all anhidrotic horses. The current thought is that there is over stimulation of the horse’s sweat glands by stress hormones. One interesting finding is that in chronic cases of anhidrosis, sweat glands atrophy. In horses newly affected, this sweat gland atrophy is not a finding. This suggests that there may be a correlation of long term downreglations on hormone receptors on sweat glands. In addition, when a horse is moved to a northern environment, it typically resumes normal sweat production. Research has found that sweat production can be decreased with certain antibiotics and medications. Researchers have not identified any age, color, sex or predisposition for developing anhidrosis. Anhidrosis is found to have a similar prevalence in both in locally-raised versus imported horses.

Diagnosis

Anhidrosis is most often a presumptive diagnosis, based on clinical signs and a veterinary exam. The hallmark of anhidrosis is that even in situations that should elicit copious amounts of sweating, anhidrotic horses will have a minimal or inappropriate amount of sweat. Owners often notice increased respiration, high body temperature, shade-seeking behavior, and a difficulty recovery after being exercised. It is not unusual for anhidrotic horses to still have sweat in certain locations. This usually misleads owners. Partial anhidrosis is the most common presentation of anhidrosis; an owner should consider anhidrosis if his or her horse’s performance declines as temperatures increase in the summer. Chronic non-sweating horses tend to develop dry flaky skin (especially on forehead), hair loss, easily fatigue, and may have decreased appetite and water consumption. A definitive diagnosis can be made by a series of intradermal injections of terbutaline where each injection has a dilution factor. Terbutaline stimulates sweat glands, which allows the veterinarian to determine the severity of the anhidrosis. If necessary, other diagnostics include blood electrolyte levels, as well as skin biopsies to evaluate the horse’s sweat glands.

Management and Treatment

In the past, the only treatment for anhidrosis was to move the horse to a cooler climate. This helps the horse to manage high body temperatures, and interestingly many horses start to sweat once in a cooler environment. In Florida, it is essential that non-sweaters are carefully managed to prevent hyperthermia (overheating). Management tools include allowing horses access to water sources (big water troughs or ponds), as well as having constant access to clean and cool drinking water. It is also recommended to feed electrolyte and salt mixture to ensure the horse maintains appropriate electrolyte concentrations. Exercise should occur when ambient temperatures are lower- early or late in the day. Turnout should be limited to night or when the temperature is cooler, and fans and misters should be provided. Other tools used include feeding dark beer, thyroid supplementation or supplements (True Sweat, One AC). Unfortunately success with these treatments is mostly anecdotal and there’s no research to support their efficacy. There has been numerous trials of different medications, but those have generally been unsuccessful. Our practice utilizes acupuncture to stimulate and maintain sweat production. We also use a herbal remedy, New Xiang Ru San, as a maintenance therapy in between acupuncture treatments. A recent study at the University of Florida found that acupuncture and herbal therapy had improved sweating in recently anhidrodic horses; however this study showed it was important to continue therapy on a regular basis to maintain success. Ideally, horses with a history of showing signs of anhidrosis should be started on acupuncture and New Xiang Ru San prior to high ambient temperatures, to prevent the horse from completely shutting down sweat production and minimize heat stress.

More information available on Dr. Kurtz’s Equine Wellness: Anhidrosis and Other Summer Medical Issues video.