Equine Wellness: Laminitis

Laminitis is a condition caused by inflammation of the laminae, which are the interlocking folds or projections between the hoof wall and the underlying soft tissues that support the bones and other internal structures of the distal limb. This inflammation weakens the zipper-like connection, allowing the bone to shift, sink, or rotate within the hoof capsule. The condition is extremely painful, resulting in lameness and in some cases becoming life threatening.

Causes of laminitis:

The most common and preventable cause of laminitis is over conditioning. Carrying extra weight not only puts extra strain on the support structures of the hoof, but horses that are overweight generally have higher circulating levels of stress hormones that cause inflammation, as well as predisposing them to other metabolic conditions, such as insulin resistance.

Equine metabolic syndrome, a condition similar to type II diabetes in humans, is common in horses and ponies that are oversensitive to feed and forage that is high in carbohydrate content. They are often “cresty necked” and have excessive regional fat deposits. Unlike humans however, horses will just create more and more insulin in response. High circulating levels of insulin then disturbs hoof lamellar metabolism, causing chronic inflammation.

Equine pituitary pars intermedia dysfunction (formerly Equine Cushing’s disease), which is caused by neurodegeneration, is another common cause of laminitis. PPID leads to high levels of several hormones, and can cause abnormal fat deposits and insulin dysregulation.

Grain overload, or any condition that causes acute inflammation, fever, or circulating endotoxins, can also cause inflammation of the laminae, increasing the risk of acute laminitis.

Corticosteroid administration in horses with other health problems such as EIAD (Equine Inflammatory Airway Disease – commonly known as “heaves”) can also cause an increase in circulating glucose and insulin levels. This is particularly true for horses that are already experiencing, or at risk for, equine metabolic syndrome.

Horses that are experiencing single limb lameness (such as after an injury) are also at risk of developing laminitis in the supporting limb. This has to do with the increased stress/weight and resulting decreased circulation (from minimal periods of rest) in the supporting limb, as well as altered glucose metabolism.

Prevention:

The hallmark of prevention of laminitis in healthy horses is maintaining a healthy weight, adequate exercise, and balanced nutrition. This is especially important for ponies and miniature horses.

Identifying equine metabolic disease and PPID early can also help prevent laminitis, or at least reduce the disease’s severity. This can be addressed by your veterinarian with a variety of blood tests, such as endogenous ACTH, blood glucose, insulin, cortisol, and TSH levels.

Diagnosis:

Physical Examination of your horse by your veterinarian will often identify a suspicion of laminitis – in combination with increased digital pulses, reluctance to walk, and favoring both front feet (typically). Confirmation is often made through more advanced testing such as applied pressure with hoof testers, distal limb nerve blocks, and radiographs. Radiographs are especially helpful in determining the degree of rotation and/or sinking, identifying any other hoof pathology, and visualizing areas of infection/abscessation that commonly occur with the condition. The initial radiographs are very important to help your farrier address rotation and to use as a baseline for monitoring the progression of the disease process and response to treatment. Displacement and rotation of the distal phalanx (coffin bone) can determine the overall prognosis for the horse as well as how aggressively the horse may have to be treated.

Treatment:

Similar to the causes of laminitis, treatment of the disease is also multifactorial. The hallmarks of conventional treatment include treating any underlying disease processes (such as PPID, EMS, or other lamenesses), weight loss, dietary management, and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication (phenylbutazone, flunixin, or firocoxib). Alternative treatments such as acupuncture, Chinese herbs, and chelation therapy are often even more effective than conventional therapy in the case of laminitis, decreasing pain, promoting healing of the laminae, and helping to prevent abscessation.

Working with your farrier is also especially important as they can often make adjustments to hoof angle, and provide supportive and corrective shoeing to help improve your horse’s level of comfort. Acute cases often benefit from icing or standing in cold water baths to help with vasoconstriction and reduce inflammation.

Refractory cases may require more advanced treatments or intervention in order to improve a horse’s comfort level and ultimately preserve their quality of life. This may include considering advanced farrier techniques, or even surgical intervention.

A surgical option for refractory, chronic laminitis cases is a deep digital flexor tenotomy. This involves transection of the deep digital flexor tendon to reduce the pull on the distal phalanx and prevent further displacement within the hoof capsule. The surgery reduces the shearing forces on the dorsal aspect of the foot which causes separation of the laminae, and lowers the heel, allowing it to return to a more normal position and reduce risk of penetration of the distal phalanx through the sole. This is often used for horses that can be salvaged for breeding, but in some cases horses can return to an athletic career.

Article written by Dr. Brown, with contributions by Dr. Francheville.

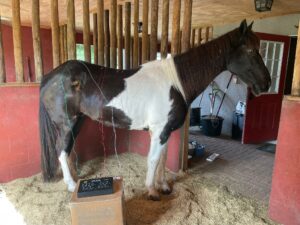

*Pictured above is “Handsome” being treated for laminitis with electrical acupuncture.