Strategic Deworming

A deworming strategy is an essential part of your horse’s health program. Your horse’s deworming schedule depends on your management system and the parasite loads of individual horses pastured together. Important considerations are the age and health status of treated horses. Typical deworming strategies target small strongyles, Ascarids (large roundworms), Gasterophilus (bots) and tapeworms. Types of dewormers are selected based on active ingredients which target each specific type of parasite. A deworming strategy is an essential part of your horse’s health program. Your horse’s deworming schedule depends on your management system and the parasite loads of individual horses pastured together. Important considerations are the age and health status of treated horses. Typical deworming strategies target small strongyles, Ascarids (large roundworms), Gasterophilus (bots) and tapeworms. Types of dewormers are selected based on active ingredients which target each specific type of parasite.

Small Strongyles:

Small (less than 1” in length) red worms that affect adult and young horses. These parasites occur in large numbers (30,000-100,000) in the large intestine. Small strongyles are known as “thieves” rather than “killers” since they typically cause ill-thrift, colic, and diarrhea. Death from this type of parasite is rare. Larvae live on the pasture and are easily killed by extreme climate, whether that be too hot, too cold, or too dry. In Florida, the greatest number of infective larvae are found from November to April. Pastures are essentially free of larvae during the summer months. The opposite is true for northern climates.

Ascarids (Large Roundworms):

Large (6”-9” in length) tan worms that primarily affect foals less than 6 months old. Most adult horses appear to be immune to Ascarids. Ascarids inhabit the small intestine. Compared to small strongyles, Ascarid eggs are extremely tough. Typically, eggs can live one or more years on pasture, and are not affected by climate. Transmission can occur year round. Usually this year’s foal crop are infected with eggs passed during the previous year. Clinical signs include weight loss, ill thrift, snotty nose, pneumonia-like symptoms, and colic with intestinal obstruction and death.

Gasterophilus (Bots):

Horse bots are the larvae of bot flies. The adult flies (Gasterophilius) are not parasitic and cannot feed. They lay and glue their eggs on the hairs of almost any part of the body, but mostly forelimbs and shoulders. These eggs are stimulated to hatch by the animal’s licking, and make their way into the mouth. From there, the larvae migrate into the stomach and small intestine, where they attach themselves. The larvae develop for 8-10 months, after which time they are passed in the feces, pupate, and become adult flies. The larvae cause damage when they attach to the stomach lining, inclusive of erosions and ulcerations around the attachment site, as well as an immune reaction. In addition, horses can develop erosions at migration sites of the larvae. Horse bots are difficult to diagnose via fecal examination. Presence of yellow egg packets on hair or signs of gastric inflammation during winter months are indicative of infestation. In Florida, transmission is thought to occur year round. Current recommendations are to treat at least once annually, at the end of bot fly season. In Florida, where the bot fly season is longer, additional treatments may be necessary.

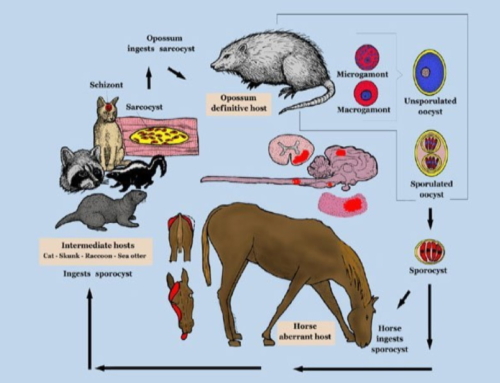

Tapeworms:

Tapeworm larvae develop within an intermediate host, the forage mite. Horses become infected while grazing and ingesting the forage mite. After ingestion, the larvae hatch from the mite and develop into adult tapeworms. The adult worms are usually found in the small intestine and cecum. There are usually no clinical signs if a horse has a light worm burden. However, with heavy infestation, horses may be thin, have a poor hair coat, and become anemic. Heavy infestations have also been associated with GI ulceration, perforation, and colic. Diagnosis can be made by identifying egg packets in feces- however these egg packets are only shed sporadically. It is difficult to identify tapeworms on fecal float or fecal egg count. There are blood and saliva tests that can be used to detect the presence of tapeworms. However, more frequently we use timed deworming to treat for tapeworms.

Theory of Refugia:

In the past few years, there has been growing concern about parasite resistance to available dewormers. While it’s tempting to deworm frequently and aggressively, there are no new dewormers currently in development. The new recommendations are to develop refugia in livestock animals. Refugia is the natural population of parasites within a horse/environment that are unexposed to anti-parasitic medications. It is important to remember that while an excessive parasite burden can cause severe disease, especially in young or immune compromised animals, a few parasites will not harm a healthy adult horse. Unfortunately, parasites are like any other organism in that they are genetically diverse. Therefore, our dewormers do not have equal efficacy across the parasite population.

Consider the following:

100 Adult Worms “Dewormer A” – 85 Dead Worms 15 Surviving Worm

Generation 2: 150 Worms “Dewormer A” – 50 Surviving Worms 100 Dead Worms

Generation 3: 500 Worms “Dewormer A” – 250 Dead Worms 250 Surviving Worms

Though the above is hypothetical, it shows what occurs to the worm population given the efficacy of a hypothetcal dewormer. Only the parasites with the greatest ability to withstand the dewormer survive and reproduce. In turn, they pass the dewormer resistance to their offspring. With each generation, more and more of the total population of worms is resistant to the dewormer.

This is the importance of refugia. If the parasistes are only breeding with other parasites that survived the deworming treatment, that resistance is higher in the next generation. However, if the resistant parasites reproduce with a population that has not been exposed to the dewormer, the more susceptible parasites of the refugi population will be more likely to pass on susceptibility to the dewormer, and will effectively dilute the resistance gene in the later generations of worms.

How does this theory play into your deworming strategy? A new approach has been developed called strategic deworming. Research has shown that 20% of horses shed 80% of the parasite eggs fround in the pasture. So when deworming horses every 6 weeks, we are over-treating many horses while under treating some. Factor in the growing resistance, and it is a recipe for parasite control failure.

Strategic deworming involves:

1. Identifying “high shedders” in your herd- these are the horses most likely to be passing the highest number of parasite eggs

2. Identifying the efficacy of each class of dewormer against each type of parasite on a particular farm

3. Determining the best time to deworm your horses against a particular parasite given the life cycle of that parasite

Veterinarians perform fecal examinations and evaluate the number of parasite eggs in a particular fecal sample. From this, you horse is classified as a low, moderate, or high parasite shedder. It is recommended to have your veterinarian evaluate a fecal sample twice a year. If there is a high shedder on your property, it is recommended to complete more fecal examinations.

If you are having a parasite problem on your property, a Fecal Egg Count Reduction Test (FECRT) can be used to monitor the efficacy of dewormers used. A fresh fecal sample is taken before deworming, then again 10 days after deworming. The number of parasites are counted in each sample and then compared to evaluate if a specific dewormer is effective.